"But I didn't do anything!"

The intent argument claims that the critical distinction between a murderer and a “normal” person is that the former actually intends to kill, while the latter merely allows the “normal course of events” to unfold.

Read more ⏷

The intent argument fails when the motivations of a murderer are properly understood. Just as a tourist does not travel for the sake of traveling, a murderer does not kill for the sake of killing. A tourist travels because they expect to satisfy their urges and improve their wellbeing by traveling, and a murderer kills because they expect to satisfy their urges and improve their wellbeing by killing. It does not matter that one enjoys piña coladas while the other enjoys playing with blood. For both, the demise of another is a byproduct of their pleasure mechanism.

The intent argument also fails when the idea of the normal course of events is put under scrutiny. The normal course of events is frequently defined as what would happen if you do “nothing.” This is meaningless. If you sit around and stare at your phone all day, you are doing nothing productive, and you are doing nothing to prevent death, but you are not doing nothing. The normal course of events could be defined as what would happen if you were incapacitated by ignorance, unconsciousness, or death, but the link between the normal course of events and your moral obligations becomes unclear. Why does it matter what would happen if you were ignorant, unconscious, or dead when you are not?

Ultimately, the motivations of a murderer and a normal person are the same, and the normal course of events is no more than a fabrication used to deflect accountability for causing death.

"But it's not just me!"

The collectivity argument claims that the critical distinction between a murderer and a “normal” person is that the former is individually responsible for causing death, while the latter is collectively responsible.

Read more ⏷

Imagine there are 100 professional swimmers watching someone drown. Every professional swimmer knows (1) that they can save the drowning person without facing any appreciable consequences and (2) that none of the other professional swimmers are going to save the drowning person.

If no one intervenes, as part of a collective, every professional swimmer is “only” 1% responsible for the drowning, but the total responsibility is 100 times greater than if there were only one professional swimmer. Why? Because the presence of others only affects individual responsibility insofar as it affects the calculus of a decision. Since every professional swimmer fully believes (1) and (2), the presence of others is irrelevant. Every professional swimmer is a murderer.

Now, imagine there are 100 gang members ordered to carry out an assassination. Every gang member fully believes (1) that they cannot sabotage the assassination without being killed and (2) that none of the other gang members are going to sabotage the assassination.

Again, if no one intervenes, as part of a collective, every gang member is only 1% responsible for the assassination, but the total responsibility is 100 times greater than if there were only one gang member. In this hypothetical, however, the presence of others does affect the calculus of a decision. Because assassination and sabotage are both fully believed to result in death, every gang member is not a murderer in the same way every professional swimmer is a murderer. Indeed, if self-preservation is sufficient reason to kill, the gang members are not even murderers.

The morality of killing is a spectrum with those who expect no trade-offs from preventing death (e.g., the professional swimmers) on the immoral end and those who expect high trade-offs from preventing death (e.g., the gang members) on the moral end.

Now, consider the billions of people with unnecessarily high human footprints. It is possible for these people to eliminate their human footprints entirely—to donate more money, to donate more biomaterials, to emit less carbon, to have less children—but it is often not pleasurable. Usually, we call people who kill for pleasure “murderers.”

"But I didn't know!"

The ignorance argument claims that the critical distinction between a “normal” person and a murderer is that the former kills knowingly, while the latter kills unknowingly.

Read more ⏷

This line of reasoning is valid. If you are still ignorant after interacting with this website, you are still innocent. However, in my opinion, most of the ignorance surrounding our human footprints is willful.

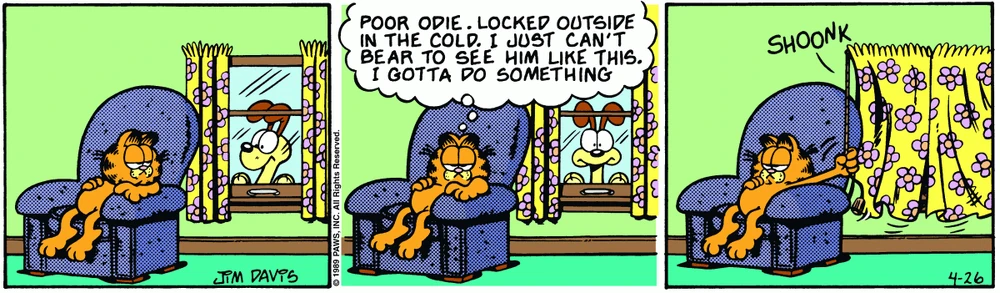

Garfield, April 1989